Table of Contents

The exact origins of print are hard to pin down,

and there is much debate over what exactly qualifies as print’s most rudimentary forms. As print developed independently in widespread civilizations throughout the world, it evolved using an enormous variety of techniques and materials.

In any case, the earliest examples of instruments for printing multiple duplicate images date back to 3000 BC Mesopotamia, when cylindrical seals were intricately carved from stone and rolled out to imprint clay. Similar image reproducing techniques are believed to have existed in cultures throughout the world, predominately using small stamps to impressive images on cloth, but few artifacts survive today.

The Emergence of Block Printing

The next major event to take place in the medium of print doesn’t arrive until 175 AD when Emperor Ling of China decrees the Confucian classics be carved in stone slabs to preserve them for posterity. The unanticipated consequence is the world’s first documented print circulation. Thousands of Confucian soldiers made rubbings of the texts, creating pages on which words appear as negatives, white against the black background.

credit: Wikipedia

Later, in 220 AD during the Han Dynasty, wooden blocks were carved and implemented to print flowers on silk––the earliest examples of wooden block printing. In India around 600AD, (where wooden block printing was never used) short Buddhist prayers and charms began to be printed using molded clay tablets. But paper texts only arrived in 750AD, when Korean Buddhists were responsible for printing the first single-page document. Japan, a country rich in wood and paper, followed suit, and in 768 was able to circulate a similar single page document to an audience of nearly 1 million––an unprecedented feat for the time.

segment from the Diamond Sutra. credit: Wikipedia

But the biggest accomplishment of wooden block printing occurred in 868 AD China, when the “Diamond Sutra” was created: the world’s first printed scroll-form book. The next block printed books later appeared in Japan in 1052. But printing was slow to take hold in the West, and European block printing on paper didn’t begin until the 1400s. The first fixed-type printed Western books wouldn’t appear until around 1500.

Moveable Type

Moveable type represents a vast improvement over block printing because it allows for much more flexibility and a greater range of printing options. The first moveable type (made from porcelain) was designed by a man named Bi Sheng in 1040. The first metal moveable type subsequently originated in Korea in 1230, during the Goryeo Dynasty. However, because Eastern languages have such extensive and intricate character sets, these early moveable types were inefficient and did not provoke a major revolution in printing at the time.

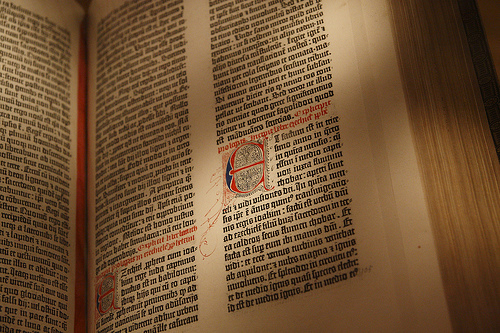

Gutenberg Bible. credit: jmwk

But Western languages had a distinct advantage in this regard, and––though it took another two hundred years––when Gutenberg invented the first European moveable type in roughly 1440, it provoked a massive revolution in print and the circulation of written information. Gutenberg’s printing press also made the important innovations of using type smelted from an alloy of tin, lead, and antimony, and the implementing an oil-based, as opposed to water-based, ink. Both new techniques made the Gutenberg printing press a durable and reliable machine, capable of producing the massive volumes of text that it was responsible for.

Today, print continues to evolve and is drifting ever farther into fluid forms. Just as moveable type allows for more flexibility than block printing, the digital revolution has made type moveable in ways that were unimaginable a century ago. We now have the ability to read and write non-physically with computers, and alter the look and design of our fonts with the click of a button. Not to mention the vast circulations that are possible in the Internet age. There is no question that print will continue to change and improve as human innovation finds better ways to express itself in written language.